I settled into my hammock a couple of weeks ago, ready to enjoy a glass of iced tea (with chocolate mint from my garden), a good book, and some peace and quiet. Until I heard a pulsing hum in the distance. With a sigh I tried to ignore what I assumed was some sort of motor noise from a distant neighbor’s yard. The pulsing wasn’t loud, but it was continual and somewhat irritating, since too often I feel inundated by various types of engine noise that drown out the quieter sounds of nature and eliminate silence from my world. It occurred to me that it might be some sort of insect sound, but it seemed so regular in its pulsing that we figured it must be an engine.

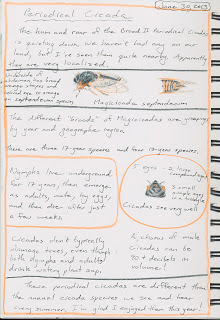

The next afternoon the motor noise was louder, and I began to think it might be the 17-year cicadas I had been reading about, but I wondered why I hadn’t seen any in our yard. When I went for a walk around some neighboring roads, though, the humming was much louder in some areas and almost nonexistent in other areas, even along a two-mile loop. And, I began to see a few red-eyed cicadas. It turns out that these periodical cicadas can be very localized and may emerge with great density in some areas and be completely absent in immediately adjoining areas.

Interestingly, once I knew the noise I was hearing was a cicada chorus and not a motor running loudly in the distance, it no longer seemed irritating. Now I wanted to hear it more closely and see more of these red-eyed singers, more fully experiencing this brief and fascinating visitation of long-lived insects.

By yesterday the chorus was dying down and I began seeing dead and dying cicadas on my morning walk, so I brought a few dead insects home to sketch. I also looked them up and found out that there are both 13 and 17 year cicadas, with three species of 17-year cicadas and 4 species of 13-year cicadas. One fact I found particularly fascinating is that all these species have life cycle lengths that are based on prime numbers (13 years and 17 years). I just love the way math shows up in nature cycles and systems and structures!

I am sorry to say good-bye to the cicadas and their song, and I look forward to seeing and hearing their offspring in 2030.

|

| Click image to enlarge |

Interesting links with more information:

www.magicicada.org

http://cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/06/03/ask-about-the-17-year-cicada/?_r=0